In Washington State the Mockingbird doesn't fly

Conservatives and Progressives have "banned" together on at least one issue, there are books they don't want us to read.

WASHINGTON STATE – In Ray Bradbury’s 1951 dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, the protagonist is a firefighter whose job is not to put out fires and save citizens from burning buildings, but instead to save citizens by burning books the government doesn’t want to be read.

While the government is not burning books…yet, Americans have been busy trying to ban all kinds of books that someone— a parent, a teacher, a student — doesn’t want to read, or don’t want you to read.

According to a recent report by PEN America, a writer’s advocacy organization, there were “more school book bans during the first six months of the 2023-24 school year than in all of 2022-23.” And the American Library Association said in a press release that “the number of unique titles targeted for censorship surged 65 percent in 2023 compared to 2022, reaching the highest levels ever documented by ALA.”

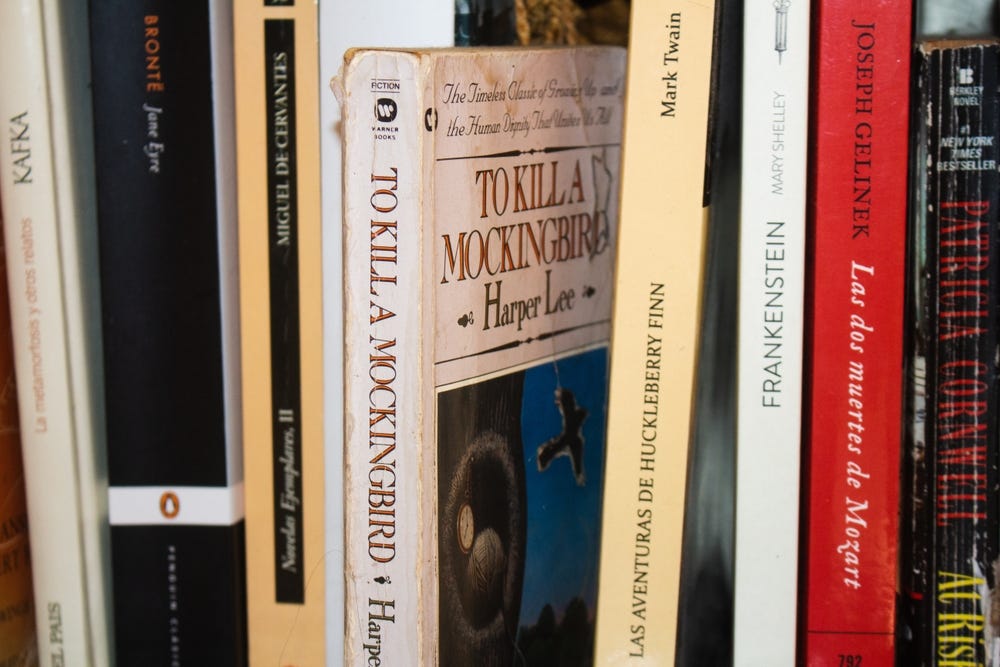

Killing the Mockingbird

Conservatives are often blamed for the book banning orgy — but progressives have also been busy trying to silence some of our most famous authors and our most compelling stories. They've just used different tactics.

Take, for example, what’s happened in Washington State. A group of four progressive English teachers attempted to ban the book To Kill a Mockingbird from the high school’s curriculum.

“To Kill A Mockingbird centers on whiteness,” the teachers complained, “it presents a barrier to understanding and celebrating an authentic Black point of view in Civil Rights era literature and should be removed.”

“Around the country, book challengers mostly came from the right,” Hannah Natanson wrote in the Washington Post, “But in Mukilteo [Washington], the progressive teachers who complained about the novel saw themselves as part of an urgent national reckoning with racism, a necessary reconsideration of what we value, teach and memorialize following the killing of George Floyd…They believed they were protecting children.”

Not unexpectedly, there was pushback. “Any time you restrict access to students, it’s unfair,” a local school librarian told The Post, “This was, to me, a form of censoring.” After the challenge some teachers, wrote Natanson, were scared to assign Mockingbird for “fear of being labeled racist.”

In 2021 readers of the New York Times voted Mockingbird the best book of the last 125 years. From day one Mockingbird has been controversial — many Whites didn’t like being called on their racism — some objected to the portrayal, or even the mention, of rape. Some Blacks (and Whites) objected to frequent use of the n-word, and what was thought to be a shallow portrayal of Black characters. Some even objected to a White woman writing about Black men.

“Over the years, opponents of the book have argued its 48 mentions of the n-word are harmful to students, especially students of color,” says Natanson, “and that the novel focuses unduly on a ‘white savior' in protagonist Atticus Finch, leaving out the voices of the Black characters.”

Yet two Black students from a neighboring high school disagreed. Joy Matthew, a 2021 graduate of Mariner High School, wrote in an statement that “Removing ‘Mockingbird; would mean ‘silencing Tom Robinson and every black man who has been unfairly persecuted.’”

Another recent Mariner graduate, Dyonte Law, wrote in an email that “I thought it was all in my mind, [but] Harper Lee allowed me to put into perspective the idea of inherent bias, and how an entire community can be unaware of the fact that they even held a bias.”

“The fight over ‘Mockingbird’”, observed Natanson, “would spark a rare moment of national political unity, with right-wing critics alleging the district wanted to censor a classic in service of a ‘woke’ agenda — while left-wing detractors insisted teachers were erasing the reality of racism.”

Ultimately the school board voted to leave the book on its approved books list but to remove it from the required reading list.

Censorship isn’t only an issue for parents, students, and teachers, however. And it’s not only about what’s written, but also about who is writing. There are those that think that only black authors can tell black stories. “I don’t think that White authors and White characters should tell the narratives of African American people,” Verena Kuzmany, one of the four teachers calling for banning Mockingbird, said. “The usefulness of the book has run its course.”

More on this a bit later.

For every action…there’s an opposite and often unequal reaction.

While progressives were busy out on the West Coast trying to silence a White author speaking to race and racism, conservatives were busy on the East Coast trying to do the same to a Black one.

A high school AP English teacher in South Carolina found herself in the middle of what has turned into a national controversy on race, and the teaching of controversial subjects to high school students. The teacher, Mary Wood, assigned the book Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates, a controversial black author who writes about race in America, to her class.

The book is written in the style of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, which takes the form of a letter written to Baldwin's 15-year old nephew. “As an African American, he makes me proud. There is no other way to put it. I do not always agree with him, but it hardly matters,” Michelle Alexander wrote in the New York Times about Coates. He “speaks unpopular, unconventional and sometimes even radical truths in his own voice, unfiltered. He is invariably humble, yet subtly defiant. And people listen.”

No question, Coates’ book is controversial — meant to force a confrontation — a confrontation intended to make readers uncomfortable. While Baldwin’s book is hopeful about the future, Coates is pessimistic. Baldwin is angry, but sees some reasons for optimism. Coates is just angry.

In her review of Between the World and Me, Betsy Reed, an editor for The Guardian, wrote that the book is "a rather strange blend of epistolary non-fiction, autobiography and political theory that has at its heart a simple message: ‘In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body – it is heritage.’” Racism, Coates argues in his book, is inescapably woven into the fabric of White culture.

New York Times book reviewer Michiko Kakutani, however, cautioned that Coates’ ignores “changes that have taken place over the decades.” While Coates’ argues that what was true in 1776 is true today — and rejects that any progress has been made on race in America, “Such assertions,” Kakutani wrote, “skate over the very real — and still dismally insufficient — progress that has been made.”

Is critical thinking in critical condition?

Students —White students — and their parents complained. One student grumbled that the book was “too heavy to discuss,” and that they “felt ashamed to be a Caucasian.” Another said they felt “betrayed,” and that Wood was trying to “subtly indoctrinate our class.”

Indoctrinate, seriously? The book IS written to make people feel uncomfortable, and to challenge the status quo. But is that enough to ban it from the classroom? Is expecting a student in a high school AP class to read critically, and explain whether they agree, or disagree, with the author’s position indoctrination? Or is it promoting critical thinking?

If the goal is to steer every student away from the controversial, then we can have them read Dr. Suess. Oh wait, he's controversial too!

Isn’t one of the goals of education to teach students how to deal constructively with controversial topics? For those complaining, we already know the answer. They don't want their worldview challenged.

These feelings of indoctrination or distress, however, were not universally shared among Wood’s students. “She did a really good job of keeping things not boring,” one of her students told The Post. “People spoke up and they had different opinions — I honestly didn’t hear a single complaint about the book from anyone.” The student, according to The Post, “said his peers debated systemic racism and what it’s like to be Black in America, agreeing and disagreeing with Coates, without Wood picking a side.”

Called to the assistant principal’s office, Wood was told “This assignment could run in conflict with proviso and policies…We need to cease this assignment.” At the next school board meeting, after the school term had ended and classes on the book were cancelled, several speakers criticized Wood’s assignment of the book. Some charged the selection of the book was “inappropriate and divisive, this is illegal,” and calling for her to be fired — another said she hoped the school board “were all Christians.”

“Too liberal for White people and too white for Black people.”

Must a book written by a white person only have white characters? Should a book written by a black author have only black characters?

In a Wall Street Journal Essay, the crime and legal drama writer Richard North Patterson, author of 16 New York Times bestsellers, recounts the rejection of his novel Trial, which “concerns the televised trial of an 18-year-old Black voting rights worker, stemming from the fatal shooting of a White sheriff’s deputy during a late-night traffic stop in rural Georgia.”

“The narrative,” explains Patterson, “addresses charged racial issues: voter suppression, the abuse of police power, the mass exploitation of racial anxiety, and the difficulties of Black defendants in controversial cases.” Two of its three main characters are black.

The book, says Patterson, was rejected by no less than 20 publishers. Some of the publishers commented that he would be “rightly criticized” for writing the book, or that they only wanted to hear from “marginalized voices.” Another said he was “too liberal for white people and to white for Black people.”

Should books be canceled before they are written?

Should authors abandon putting non-white characters in their books? Or just White authors? What about men writing about women, or women writing about men? Can a straight person write about gay characters, or a gay writer about straight ones? Should empathy and imagination," Patterson wonders, "be allowed to cross the lines of racial identity?”

And what if books could be cancelled before they are published, even before they are written? “If the preemptive censors triumph,” Patterson worries, “there will be fewer books to read, not just those that are canceled but those never written for fear of cancellation.”

Despite what Patterson describes as a “serious journalistic commitment” to creating a “credible, sensitive, fictional” account, “I had no illusions that this would immunize me from a new phenomenon in publishing: the belief that white authors should not attempt to write from the perspective of nonwhite characters or about societal problems that affect minorities.”

“If the preemptive censors triumph, there will be fewer books to read, not just those that are canceled but those never written for fear of cancellation.”

Richard North Patterson

Have we now moved from banning books to banning authors? Or at least banning the kinds of stories that authors might want to tell? Will there be a racial litmus test before a book is even published? That would certainly cut out one book banning step, banning them before they are even published.

Patterson poses an important question. “Isn’t one purpose of literature to inspire readers to see ‘the other’ differently?” Zadie Smith, a black author whose books have been shortlisted for Britain’s Booker Prize, and who teaches literature at NYU, dismisses the adage “Write what you know,” which “is now used to keep novelists within the bright chalk circle of personal identity.”

Smith “similarly warned us off the absolutist belief, vaguely burbling up among her writing students,” Andrea Lang Chu wrote in Vulture, “that a novel’s characters should be judged for how ‘correctly’ they represent the distinctive behaviors of an identity group…How can such things possibly be claimed absolutely unless we already have some form of fixed caricature in our minds?”

The Silent Majority.

Recent polls show that a majority of Americans, a large majority, reject the idea of banning books. According to a CBS News Poll. “Large majorities — more than 8 in 10 — don't think books should be banned from schools for discussing race and criticizing U.S. history, for depicting slavery in the past or more broadly for political ideas they disagree with. We see wide agreement across party lines, and between White and Black Americans on this. Parents feel the same as the wider public.”

The problem? These aren't the people showing up at school board meetings, or holding protests outside libraries, or attending faculty meetings on curriculum.

For its part, much of the mainstream media portrays book banning as a part of the conservative playbook. “It’s hard to disentangle the banning surge from other conservative efforts to use the government to limit expression,” Alexandria Alter, who covers publishing for the New York Times, said.

But perhaps Alexandria should read Patterson’s essay in the Journal, or The Washington Post's story on efforts by progressives to ban To Kill a Mockingbird. Book banning has become bipartisan.

Who decides?

While much of the popular controversy has centered on efforts to remove books some find offensive from public, or school, libraries — this is not to say that there aren’t some books that are inappropriate for certain ages, or inappropriate for a school library. But who should decide? Not every challenge to a book is partisan, or wrong.

According to the American Library Association’s (ALA) policy, “Librarians and governing bodies should maintain that parents—and only parents—have the right and the responsibility to restrict the access of their children—and only their children—to library resources.”

However, the ALA also offers guidance to school librarians in both selecting books for libraries and responding to challenges to books already in libraries. The ALA suggests that books ”Be appropriate for the subject area and for the age, emotional development, ability level, learning styles, and social, emotional, and intellectual development of the students for whom the materials are selected.”

But that’s not what we’re talking about here. We are talking about censorship — restricting what other students are exposed to because the topic might make one student, or more often some adult, uncomfortable — or challenge some political or social orthodoxy.

We’re also talking about efforts to preemptively censor authors — or putting some topics off-limits — if the author doesn’t have what someone else considers the appropriate racial, ethnic, gender, or whatever, “identity.”

Like flies to…well, you know...

Like flies to, well, you know what — politicians of both parties are drawn to the book banning controversy. If there isn't a crisis, worry not; Politicians will invent one.

“Book bans are on the rise in U.S. schools, fueled by new laws in Republican-led states,” exclaims an LA Times article. The Associated Press reports that “lawmakers in more than 15 states have introduced bills to impose harsh penalties on libraries or librarians.” Some states, like Illinois, have gone in the opposite direction, passing legislation banning book bans.

According to a Washington Post analysis of state legislative databases, and a library advocacy group EveryLibrary, legislators in at least 22 states have proposed 57 bills to either ban book bans or prohibit the prosecution of librarians. And, The Post reports, at least 27 states are considering bills that “restrict which books libraries can offer and threaten librarians with prison or fines,” for providing access to “obscene” or “harmful” books.

While The Post “could not find an instance in which a librarian has been charged under these laws,” there have been instances where “police were called to schools or launched investigations over books — in Missouri, Texas and South Carolina.”

Are there books that shouldn’t be in school libraries, or perhaps unavailable to children? Sure. But what about books that tell a story that someone doesn’t want you to hear because it conflicts with their worldview, makes them uncomfortable, or is in conflict with their notion of who is entitled to tell a story — books like To Kill a Mockingbird, Between the World and Me, or James Patterson’s Trial?

Do we really need legislation telling us what books we can read or stories we can tell? And are we really going to start fining, or worse, throwing librarians in jail—or banning books even before they are written?

“There is more than one way to burn a book,” Ray Bradbury warned, “And the world is full of people running about with lit matches.”